A 65-year-old male with HIV presented to clinic with several pruritic, scaly papules of two weeks’ duration. Recent HIV viral loads were undetectable. The patient reported being treated for syphilis in the 1990s and again in 2020. Previous rapid plasma reagin (RPR) results were not readily available at the initial clinic visit. He denied any other skin concerns. Physical examination revealed two pink papules on the left chest (Figure 1), two hyperpigmented scaly papules on the left leg and back, and one dark brown macule on the right palm.

Figure 1. A pink papule on the left chest.

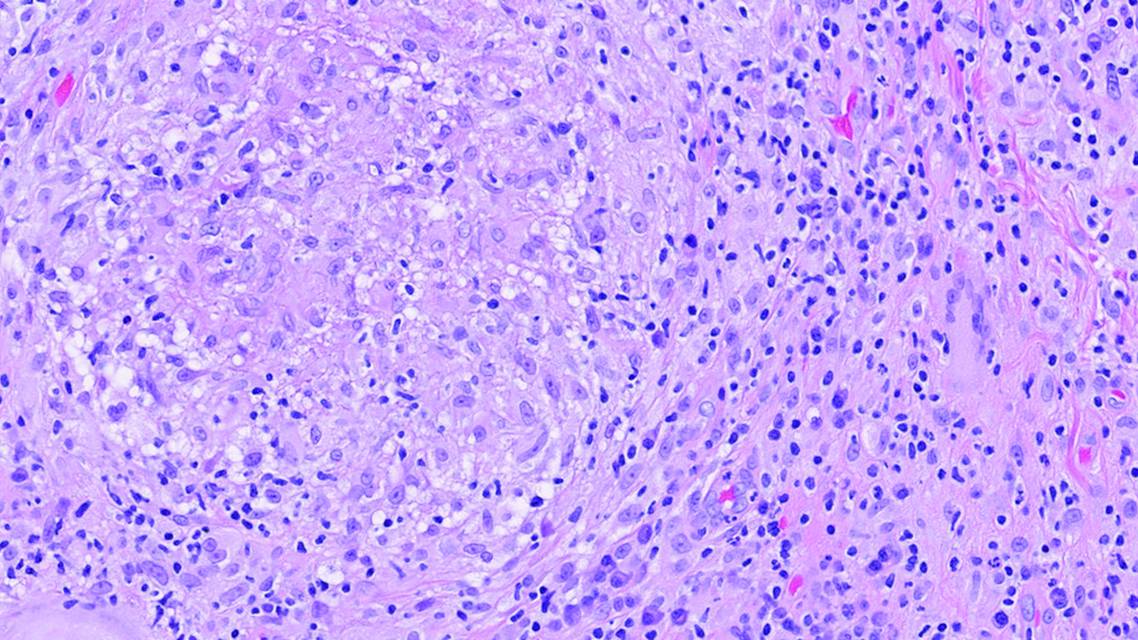

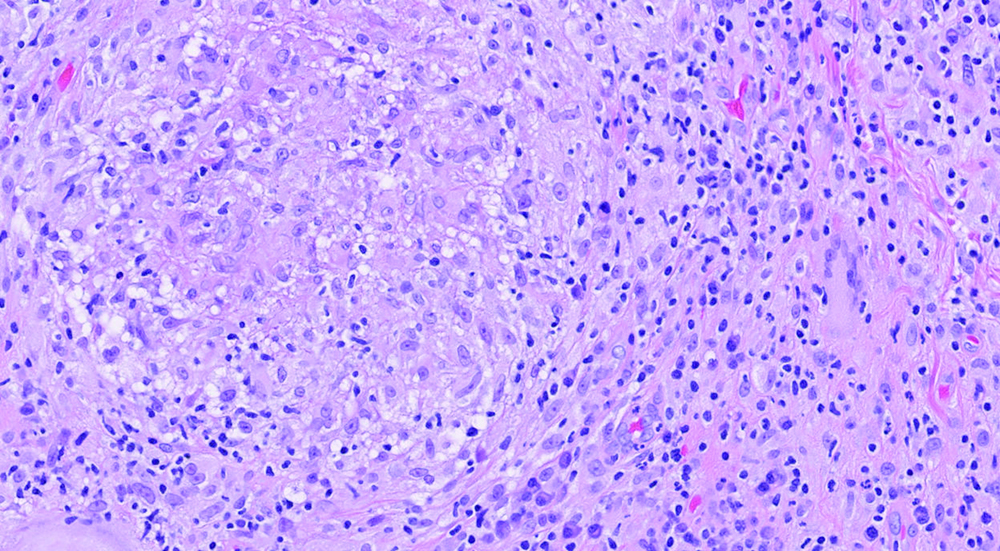

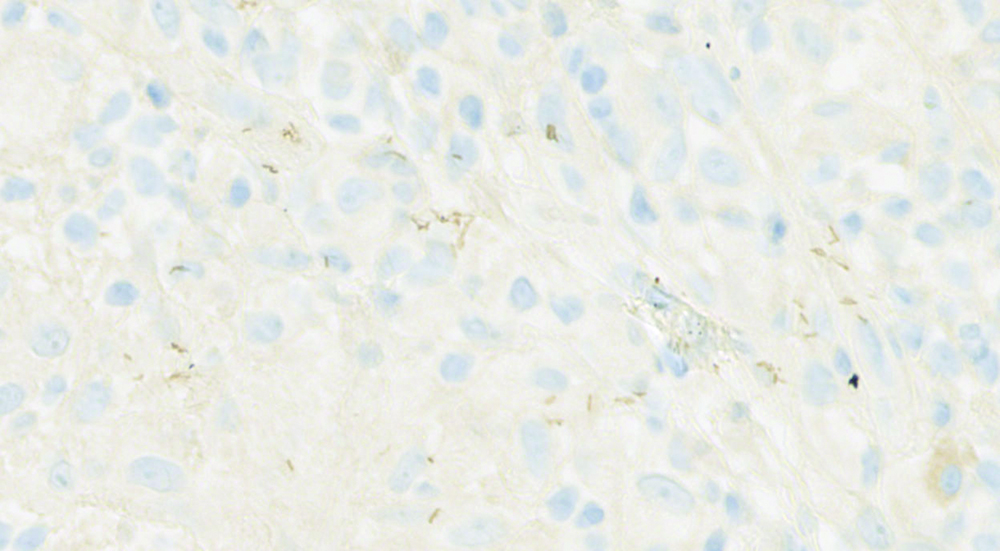

Given the patient’s recent syphilis infection and subsequent treatment within the setting of HIV, there was a concern that his symptoms represented either failure of treatment or reinfection. A punch biopsy of the left chest lesion revealed noncaseating granulomatous dermatitis with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemistry for treponema demonstrated microfoci of spirochetes (Figure 2B).

Figure 2A. A noncaseating granuloma with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates [H&E, original magnification x20].

Figure 2B. Treponemal IHC immunostaining showed microfoci of spirochetes [Treponema IHC, original magnification x50].

The patient was able to provide RPR levels obtained in 2021, which were nonreactive. A repeat RPR titer after initial clinic visit was found to be reactive at a 1:256 dilution, indicating a significant elevation from 2021. Given the constellation of clinical, histologic, and laboratory findings, a diagnosis of secondary syphilis was made. The patient was treated with 2.4 million units of penicillin G IM in the clinic. Five months after the initial visit, skin evaluation noted significant improvement in his skin lesions. A repeat titer post-treatment showed a fourfold decrease to 1:32, confirming an adequate response to treatment. The patient was also counseled to inform all sexual partners of the need for treatment and to continue follow-up with an infectious disease clinic for HIV therapy.

Discussion

Syphilis is a sexually and congenitally transmitted disease caused by the spirochetal bacterium Treponema Pallidum. In the past two decades, the prevalence of syphilis has markedly risen in the United States.1 Primary syphilis is the first stage of disease commonly characterized by a single chancre lesion at the site of sexual contact.2 Secondary syphilis follows 6 to 8 weeks after chancre resolution with symptoms that can include fever, headache, and a morbilliform rash. Untreated patients can enter an asymptomatic latent phase of syphilis that can last several years.3 Approximately one third of untreated patients will ultimately develop tertiary-stage symptoms of syphilis, marked by gummas—chronic lesions that can occur anywhere on the body, including the skin and internal organs—and progressively damaging neurological and cardiovascular conditions.3,4

Diagnosis of syphilis is largely clinical with support from laboratory tests. However, clinical diagnosis of syphilis proves to be a challenge due to its reputation as “the Great Imitator.” Cutaneous manifestations of syphilis are common and involve a diverse set of nonspecific morphologies that mimic other skin conditions. Pink papular lesions that range from 1 mm to 20 mm in size present frequently on the flanks and extremities, and less commonly on palmoplantar regions.4 These lesions often have a thin, scaly ring known as “Biette’s Collarette.”5

Lichen planus is a chronic, inflammatory skin condition that is included on the differential due to its striking similarities with violaceous, flat, scaly lesions that can appear on palmoplantar surfaces.6 Similarly, lichen planopilaris can cause destruction of hair follicles on the scalp that resembles the diffuse “moth-eaten” alopecic manifestation of syphilis.7 Hallmark histopathology involves a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate at the dermal-epithelial junction and saw-toothed irregular rete ridges.

Sarcoidosis is a chronic, multi-organ disease marked with granuloma formation; the skin is the second most affected organ.8 Cutaneous sarcoidosis diagnosis must be confirmed with skin biopsy and histologic examination, which commonly demonstrates non-necrotizing granulomas with epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells bordered by a mild lymphocytic infiltrate. In rare cases, syphilis can present with diffuse folliculitis resulting from follicular tropism of treponemal spirochetes.9 Although uncommon, it is important to recognize folliculitis as a possible symptom of secondary syphilis. Immunosuppression, especially in HIV infection, may predispose patients to develop eosinophilic pustular folliculitis characterized by erythematous, pruritic papules.10 Histological observations show follicular inflammatory infiltrates with eosinophils.

Secondary syphilis may also be mistaken for psoriasis, particularly with palmoplantar surface involvement. One literature report describes a case of clinically diagnosed psoriasis that failed to improve with typical anti-psoriatic medication.11 Further examination revealed Biette’s sign, leading to the correct diagnosis of syphilis. Psoriasis diagnosis also largely depends on clinical findings.12 Well-demarcated, erythematous plaques with silvery scales commonly affect extensor surfaces. Specific syphilis diagnostic testing is imperative to diagnose syphilis infection in patients with psoriasis-like presentations.

Upon clinical suspicion, laboratory techniques must be employed to further investigate potential infection with syphilis. Multiple laboratory methods exist for the screening and diagnosis of syphilis at different stages. The traditional diagnostic algorithm requires an initial positive non-treponemal test, such as a Venereal Disease Research Laboratory Test or RPR, followed by confirmation with a treponemal test such as Fluorescent Treponemal Antibody Absorption. A reverse algorithm approach starting with a treponemal test has also grown more popular in recent years due to increased sensitivity of initial testing, albeit at the cost of decreased specificity.13 For patients with prior infection, as in the case detailed in this article, measuring RPR titers to assess disease activity may be necessary as treponemal testing will often remain positive for life.14 The current treatment recommendation for syphilis is generally a single shot of Benzathine penicillin G IM with some variation to dosing and interval.2

This case raised several important clinical conundrums. The patient had been treated twice previously for syphilis infections, most recently within 12 months of initial presentation to the dermatology office. In one longitudinal study, HIV co-infection was associated with three-fold increased chances of treatment failure or reinfection with syphilis.15 We had to consider not only the possibility of a third infection, but also the potential for treatment failure in an HIV patient. When diagnosing and treating secondary syphilis, particularly under the context of HIV-coinfection, clinicians should be aware of the complexities regarding the diverse cutaneous presentations, reinfections, and treatment failure.

The authors have no relevant financial disclosures to report.

Christy Chang is from the College of Medicine at the University of Illinois College of Medicine. Dr. Waterman and Dr. Hoyer are from the Department of Dermatology at the University of Illinois College of Medicine. Dr. Braniecki is from the Department of Pathology at the University of Illinois College of Medicine.

1. Kojima N, Klausner JD. An Update on the Global Epidemiology of Syphilis. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2018;5(1):24-38.

2. Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, Johnston CM, Muzny CA, Park I, Reno H, Zenilman JM, Bolan GA. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70(4):1-187.

3. Peeling RW, Mabey D, Kamb ML, Chen XS, Radolf JD, Benzaken AS. Syphilis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17073.

4. Çakmak SK, Tamer E, Karadağ AS, Waugh M. Syphilis: A great imitator. Clin Dermatol. 2019;37(3):182-191. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2019.01.007.

5. Tognetti L, Sbano P, Fimiani M, Rubegni P. Dermoscopy of Biett’s sign and differential diagnosis with annular maculo-papular rashes with scaling. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2017;83(2):270-273.

6. Ambooken B, Asokan N, Jisha KT, Ninan L. Syphilis cornee mimicking lichen planus clinically and histologically. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2018;39(2):130-132.

7. Boch K, Langan EA, Kridin K, Zillikens D, Ludwig RJ, Bieber K. Lichen Planus. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:737813.

8. Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous Sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36(4):685-702.

9. Isler MF, Hoskins S, Esparza EM, Ruhoy SM. Syphilitic Folliculitis: A Case Report With Demonstration of Spirochetes Showing Follicular Epitheliotropism. Am J Dermatopathol. 2022;44(11):837-839.

10. Kanaki T, Hadaschik E, Esser S, Sammet S. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (EPF) in a patient with HIV infection. Infection. 2021;49(4):799-801.

11. Gianfaldoni S, Tchernev G, Wollina U, Gianfaldoni R, Lotti T. Secondary Syphilis Presenting As Palmoplantar Psoriasis. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5(4):445-447.

12. Cohen SN, Baron SE, Archer CB; British Association of Dermatologists and Royal College of General Practitioners. Guidance on the diagnosis and clinical management of psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37 Suppl 1:13-8.

13. Luo Y, Xie Y, Xiao Y. Laboratory Diagnostic Tools for Syphilis: Current Status and Future Prospects. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;10:574806.

14. Klausner JD. The great imitator revealed: syphilis. Top Antivir Med. 2019;27(2):71-74.

15. Luo Z, Zhu L, Ding Y, Yuan J, Li W, Wu Q, Tian L, Zhang L, Zhou G, Zhang T, Ma J, Chen Z, Yang T, Feng T, Zhang M. Factors associated with syphilis treatment failure and reinfection: a longitudinal cohort study in Shenzhen, China. BMC Infect Dis. 2017 ;17(1):620.

Ready to Claim Your Credits?

You have attempts to pass this post-test. Take your time and review carefully before submitting.

Good luck!

Recommended

- Clinical Case Reports

Upadacitinib Therapy in a Pediatric Patient with Infliximab-Induced Skin Eruption

- Clinical Case Reports

Orchiectomy-Induced Melasma: Considering Melasma in Male Patients Post-Orchiectomy