A Clinician's Guide to Alopecia: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention

Sarah J. Shareef, BS, and Peter Lio, MD, share tips on recognizing and treating alopecia.

Hair loss, also known as alopecia, is a prevalent condition that affects people across every demographic.1 Unlike other skin issues that may remain unnoticed for extended periods, hair loss is often immediately apparent to the patient. Recently, alopecia has gained significant media attention following an incident at the Oscars in March 2022 when comedian Chris Rock made a remark about Jada Pinkett Smith's hair loss, which is believed to be alopecia areata, sparking conversations about the condition online.2 Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a surge in cases of telogen effluvium, another common form of alopecia, further highlighting the issue and its impact on people. These developments have brought hair loss into the cultural zeitgeist, making it an increasingly relevant topic of discussion.3,4

This increased awareness may motivate patients to seek evaluation for hair loss, perhaps even in advance of actual signs. Alopecia can be difficult to diagnose and treat, even for specialized practitioners. Thus, this brief clinical review is not only for dermatologists and dermatology-focused practitioners, but also for those who are interested in learning more about navigating the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of some of the common types of alopecia.

Alopecia Diagnosis: History and Physical

When approaching a patient with hair loss, a comprehensive history and physical examination is critical to determining if the hair loss is abnormal. A good starting point is quantifying the amount of hair loss occurring. Patients can present with a concern of losing a lot of hair and sometimes can be reassured knowing that it is normal for individuals to diffusely lose 50-100 hairs each day.1,5 In addition to the amount of hair loss, both the location and the pattern are important to take into account. If the patient is losing more than the normal number of hairs per day or presents with visible areas of hair loss, further investigation is warranted.

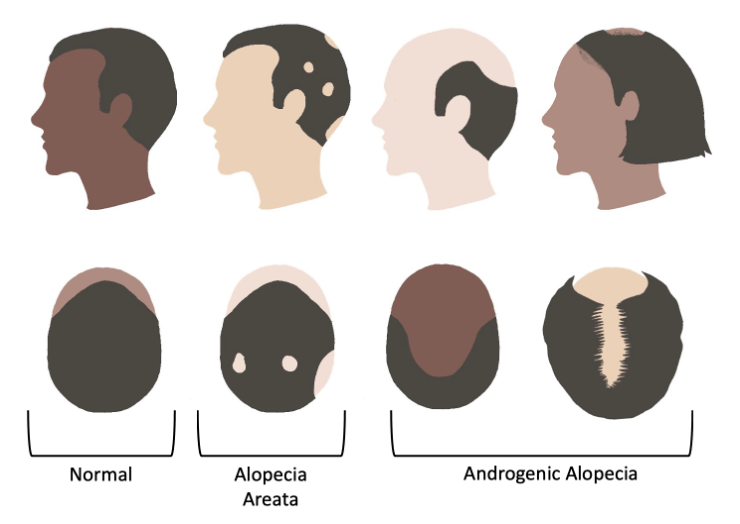

The distribution of hair loss can help guide diagnosis. Telogen effluvium is usually diffuse in nature, while androgenic alopecia (AGA) cases typically present as a receding hairline of the temporal and frontal region or vertex of the scalp in men and a widening part in women (Figure 1). Whereas in alopecia areata there may be discrete patches of hair loss or even total loss: alopecia totalis when the entire scalp is devoid of hair, and alopecia universalis when all the hair on the body including eyebrows, lashes, underarm hair, etc. is absent.1Scarring (cicatricial) forms of alopecia are most concerning as they may cause permanent loss as the hair follicles become scarred due to inflammation. They also may cause hair loss in other areas of the body besides the scalp, such as eyebrows, lashes, or body hair.6

Figure 1: Examples of characteristic distribution patterns of alopecia areata and androgenic alopecia

The timeline of lossmay be helpful to discern the inciting factors that may be contributing to the process. The powerful connection between physical and mental health is also important to consider in this analysis. For instance, diffuse hair loss due to telogen effluvium commonly occurs several months after a stressor or illness, such as following COVID-19 infection or significant weight loss.3,4

Understanding patient habits can identify areas of opportunity where adjustments can be made. The type of shampoo, conditioner, use of heat, and hairstyle all can be contributing factors to hair loss. For example, traction alopecia is a common occurrence in those who wear tight hairstyles alone or coupled with use of hair coverings such as hijabs, turbans, or wigs.7,8 This can be discerned by examining the distribution of the hair loss (usually temporal or occipital area) in conjunction with the history.

Alopecia Diagnostics

One diagnostic test that can be performed is the hair pull test . This is a simple test that can be done easily, and without equipment, to help determine the amount of hair loss. This is done by grasping 50-60 hairs between the fingers and gently pulling the hairs away from the scalp. This technique should be done on different parts of the scalp.1 While older literature often allowed up to four hairs, more current thinking is that one to two hairs being removed is considered normal when the pull test is performed, regardless of hair type.1,9 If there are more hairs than this, it can be determined that there is an increased amount of hair loss occurring and further investigation is recommended.9

Trichoscopy, a form of dermoscopy for the hair and scalp, can be useful in the diagnosis of hair loss, specifically alopecia areata (AA). A recent review of trichoscopy identified common features of AA including yellow dots, short vellus hairs, black dots, tapered hairs, broken hairs, exclamation mark hairs, upright regrowing hairs, pigtail hairs, and Pohl-Pinkus constrictions.10 In the hands of an experienced practitioner, these findings can help clinch the diagnosis without further workup.

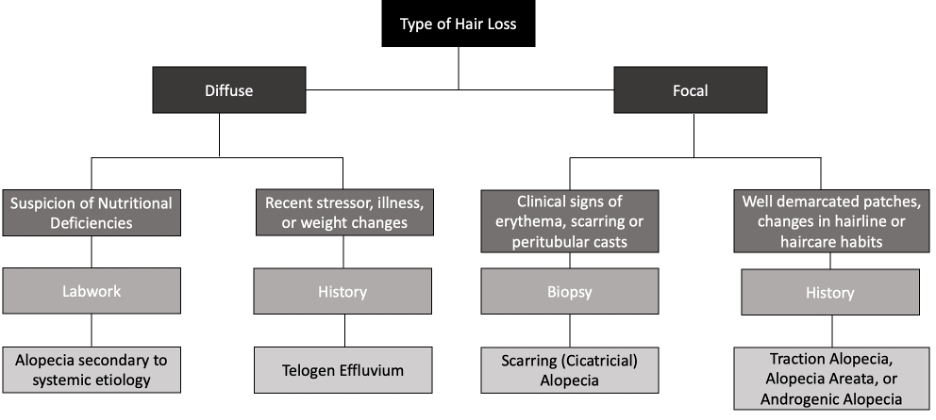

When presented with a patient with diffuse hair loss, blood work may also be a useful tool to determine underlying etiologies such as thyroid disease, vitamin deficiencies, or anemia.1,11

In the appropriate context, laboratory evaluation for thyroid stimulating hormone, vitamin D, and iron can be an important step when history alone does not point to a diagnosis (Figure 2).11,12

Figure 2: Initial workup of alopecia to determine when a biopsy, lab work, and history should be considered for diagnosis.

While in some cases, a scarring (cicatricial) alopecia can be obvious, in others–especially in those with more mild or early disease–it can be challenging. In such cases, a scalp biopsy (typically a 4mm punch) can be helpful to further characterize the type of alopecia.1,6,13 With the help of an experienced dermatopathologist, scarring versus non-scarring alopecia can generally be differentiated, and in the case of inflammatory conditions, severity can be estimated as well.6

Alopecia: Treatment

Preventable causes of alopecia can be avoided by treating the underlying cause, ideally in conjunction with the patient's primary care physician. Iron-deficiency associated hair loss can be treated with iron therapy.11In cases of hyper- or hyperthyroidism, adequate treatment can address the hair loss. Vitamins such as C, biotin, and zinc may be supplemented to treat respective underlying vitamin deficiencies and subsequent hair loss.

There are now two treatments that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) specifically for types of alopecia:Litfulo (ritlecitinib) andOlumiant (baricitinib).14

Treatment of scarring hair loss is focused on decreasing the inflammation at hand. Mild scarring alopecia can be treated with topical or intralesional corticosteroids which can be combined with other anti-inflammatory creams such as tacrolimus–although notably, moderate, severe, or refractory cases of scarring alopecia may require anti-inflammatory antibiotics or hydroxychloroquine, or even systemic immunosuppressant therapy.6

A commonly used over-the-counter treatment, minoxidil, has often been used to treat hair loss for decades with its ability to cause arteriole vasodilation. It is FDA approved for the treatment of androgenic alopecia (AGA) and off-label use of other types of hair loss such as alopecia areata (AA), scarring hair loss, and telogen effluvium. It is available topically, orally, or in a spray form making it versatile in its administration; however, a limitation of minoxidil is its efficacy only with continuous use.1,15 It can also used in conjunction with other modalities of treating hair loss such as finasteride (a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor) in the treatment of androgenic alopecia.16–18

Although there is a wide variety of treatments for alopecia, the limitation is often the cost of these treatments as they may not be covered by a patient’s insurance. A more recent treatment for alopecia is photobiomodulation (PBM) which uses light-emitting diodes or laser diodes within the visible light spectrum to infrared light spectrum in the treatment of androgenic alopecia.17,19,21Additionally, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was injected directly into the scalp for treatment of AGA with several treatments over a few months.17,22 Despite their strong efficacy, PRP and PBM are more often expensive treatments for hair loss.23,24 Efficacy of PBM and PRP can be combined with concomitant treatments such as minoxidil or finasteride to improve the efficacy of the treatments.1,19

Alopecia: Prevention

Certain etiologies of hair loss, such as traction alopecia, can be prevented by using hair protective styles that mitigate tension on the scalp. In patients that wear hijab or turban,suggest a minimal tension hairstyle underneath the head covering paired with a looser fitting covering.7,8 More sheer materials, such as satin, minimize tension and may be an alternative to cotton or nylon head coverings, if permissible.25 For those that are not able to use tension-free hairstyles, breaks from such hairstyles have also been suggested as an alternative.25 More general recommendations for the prevention of hair loss include maintaining nutritional status and diminishing stress, or minimizing the use of heating tools to prevent telogen effluvium and breakage, respectively. In a more specific scenario, scalp cooling or cold capping can be used in patients during chemotherapy to prevent chemotherapy-induced alopecia and promote hair growth following treatment.26

Alopecia: Summing It All Up

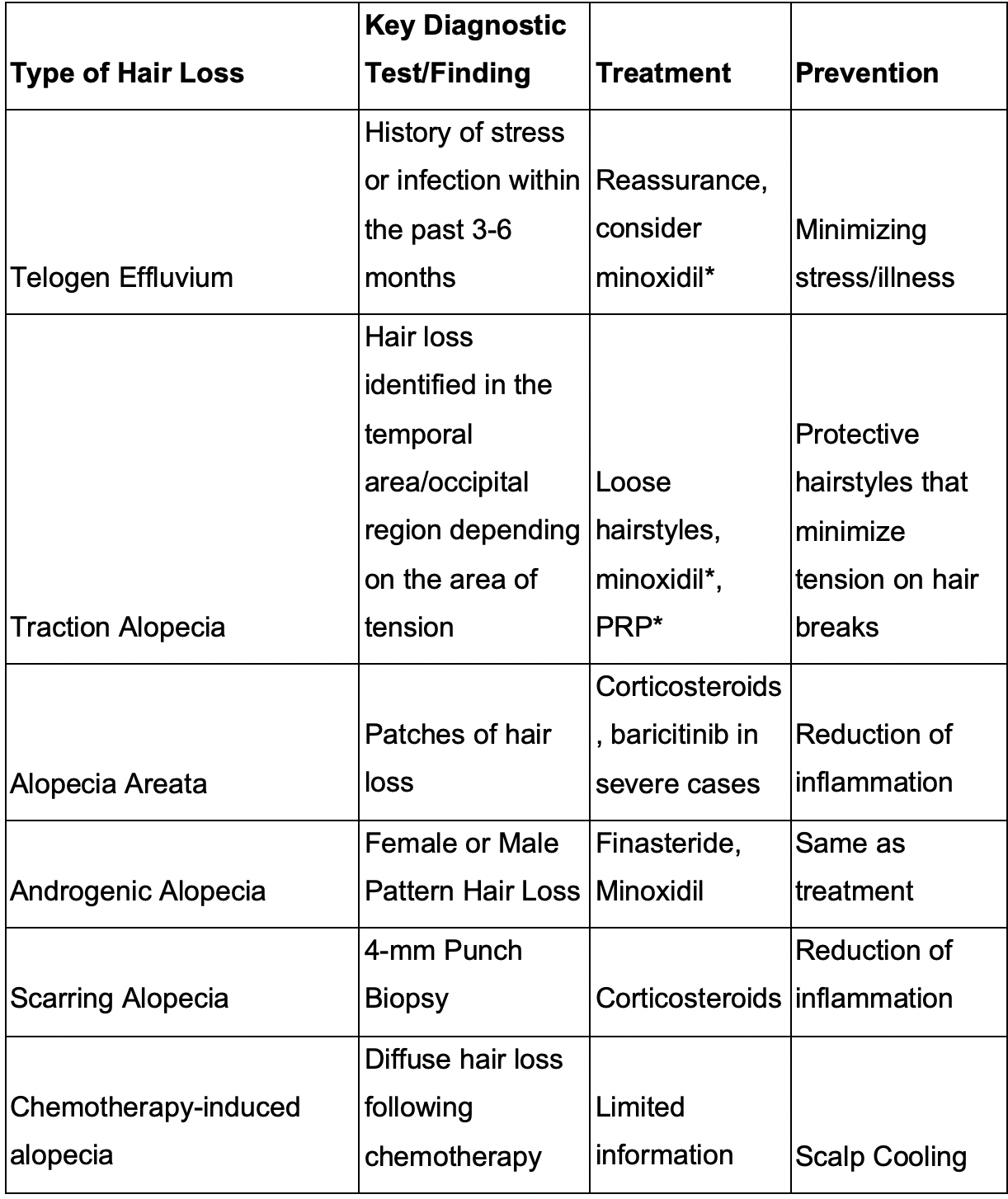

Hair loss is a complex occurrence with varying etiologies. This review highlights several common etiologies of hair loss and outlines how to discern the causes and subsequent treatment as well as preventing them from occurring in the future, summarized in Table 1. Beyond this, however, lending support to patients through the diagnosis with close follow-up, as well as establishing expectations for treatment from the start can help ensure optimal care.19

About the authors

Sarah J. Shareef BSis a medical student at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine in East Lansing, MI. Peter A. Lio, MD, is a clinical assistant professor of dermatology and pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a partner at Medical Dermatology Associates of Chicago.

Table 1: A summary of common hair type presentations, key diagnostic tests or findings, and the recommended treatment and prevention of alopecia

References:

1. Al Aboud AM, Zito PM. Alopecia. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

2. Kelly Wairimu Davis MS. Oscars Fight Highlights for Many the Toll Alopecia May Carry. WebMD. Published March 28, 2022. Accessed January 29, 2023. https://www.webmd.com/skin-problems-and-treatments/hair-loss/news/20220328/oscars-fight-shows-toll-of-alopecia

3. Mieczkowska K, Deutsch A, Borok J, et al. Telogen effluvium: a sequela of COVID-19. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60(1):122-124.

4. Olds H, Liu J, Luk K, Lim HW, Ozog D, Rambhatla PV. Telogen effluvium associated with COVID-19 infection. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34(2):e14761.

5. Cheng AS, Bayliss SJ. The genetics of hair shaft disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59(1):1-22; quiz 23-26.

6. Hordinsky M. Scarring Alopecia: Diagnosis and New Treatment Options. Dermatol Clin. 2021;39(3):383-388.

7. Shareef SJ, Rehman R, Seale L, Mohammad TF, Fahs F. Hijab, and hair loss: a cross-sectional analysis of information on YouTube. Int J Dermatol. Published online January 30, 2022. doi:10.1111/ijd.16092

8. James J, Saladi RN, Fox JL. Traction alopecia in Sikh male patients. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(5):497-498.

9. McDonald KA, Shelley AJ, Maliyar K, Abdalla T, Beach RA, Beecker J. Hair pull test: A clinical update for patients with Asian- and Afro-textured hair. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(6):1599-1601.

10. Waśkiel A, Rakowska A, Sikora M, Olszewska M, Rudnicka L. Trichoscopy of alopecia areata: An update. J Dermatol. 2018;45(6):692-700.

11. Rushton DH. Nutritional factors and hair loss. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2002;27(5):396-404.

12. Gerkowicz A, Chyl-Surdacka K, Krasowska D, Chodorowska G. The Role of Vitamin D in Non-Scarring Alopecia. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(12). doi:10.3390/ijms18122653

13. Stefanato CM. Histopathology of alopecia: a clinicopathological approach to diagnosis. Histopathology. 2010;56(1):24-38.

14. The National Alopecia Areata Foundation (NAAF).”Available treatments,” https://www.naaf.org/available-treatments-2/

15. Suchonwanit P, Thammarucha S, Leerunyakul K. Minoxidil and its use in hair disorders: a review. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:2777-2786.

16. Suchonwanit P, Iamsumang W, Rojhirunsakool S. Efficacy of Topical Combination of 0.25% Finasteride and 3% Minoxidil Versus 3% Minoxidil Solution in Female Pattern Hair Loss: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2019;20(1):147-153.

17. Katzer T, Leite Junior A, Beck R, da Silva C. Physiopathology and current treatments of androgenetic alopecia: Going beyond androgens and anti-androgens. Dermatol Ther. 2019;32(5):e13059.

18. Gupta AK, Venkataraman M, Talukder M, Bamimore MA. Finasteride for hair loss: a review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33(4):1938-1946.

19. Torres AE, Lim HW. Photobiomodulation for the management of hair loss. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2021;37(2):91-98.

20. Gokalp H. Psychosocial Aspects of Hair Loss. In: Serdaroglu ZKA, ed. Hair and Scalp Disorders. ; 2017.

21. Heiskanen V, Hamblin MR. Photobiomodulation: lasers vs. light emitting diodes? Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2018;17(8):1003-1017.

22. Justicz N, Derakhshan A, Chen JX, Lee LN. Platelet-Rich Plasma for Hair Restoration. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2020;28(2):181-187.

23. Dhurat R, Sukesh M. Principles and Methods of Preparation of Platelet-Rich Plasma: A Review and Author’s Perspective. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2014;7(4):189-197.

24. Tunér J. Is Photobiomodulation Therapy Cost-Effective? Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg. 2020;38(4):193-194.

25. Mayo TT, Callender VD. The art of prevention: It’s too tight-Loosen up and let your hair down. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7(2):174-179.

26. Novice T, Novice M, Portney D, et al. Factors influencing scalp cooling discussions and use at a large academic institution: a single-center retrospective review. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30(10):8349-8355.