At a Glance:

- Authors detail the off-label use of upadacitinib for the concurrent treatment of a drug-induced psoriasiform dermatitis and ulcerative colitis in a pediatric patient.

- Upadacitinib is FDA-approved for the treatment of adult rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and both pediatric and adult atopic dermatitis (AD).

- The patient in this case benefitted from a change from infliximab therapy to upadacitinib, seeing an improvement the psoriasiform skin reaction that sometimes occurs from infliximab infusion.

Infliximab is a chimeric IgG monoclonal antibody that binds tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-a), inhibiting binding of the cytokine and its receptor.1 This drug is commonly used to treat immune-mediated diseases, such as psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). By preventing TNF-a from activating its receptor, infliximab reduces damage caused by overactivation of the inflammatory cascade characteristic of these diseases.1,2 The most common reported cutaneous side effects are psoriasiform reactions, skin infections, and eczematous manifestation.3

Our case demonstrates the effective concomitant treatment of a patient with ulcerative colitis (UC) affected by infliximab-induced psoriasiform dermatitis with upadacitinib (Rinvoq, Abbvie). This medication has been approved by the FDA for treatment of adult rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and both pediatric and adult atopic dermatitis (AD). It was approved for treatment of UC in 2022.4 This medication is a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor, specifically targeting JAK1.4,5 Activation of the JAK/STAT pathway regulates gene transcription involved in the pathogenesis of several diseases including UC.5 This case demonstrates the effective concomitant treatment of pediatric UC and an infliximab-induced dermatitis with upadacitinib.

Case Report

A 10-year-old African American female with a history of UC treated with bimonthly infliximab infusions presented with a two-month history of a rash that started behind the ears, slowly spreading to the nose, scalp, periumbilical and groin areas. Her pediatrician prescribed terbinafine due to suspicion of a fungal infection. Several days later, the patient experienced a pruritic, papular exanthem, prompting terbinafine discontinuation and an emergency department visit.

The patient presented to the emergency department with areas of erythema consistent with a dermatophytic-like reaction to the scalp along with diffuse dried skin on the scalp and posterior ears bilaterally (Figure 1). She also had a scaling, papular rash to the forehead, chest, groin, and lower extremities bilaterally (Figure 2). This eruption began after her last infliximab infusion.

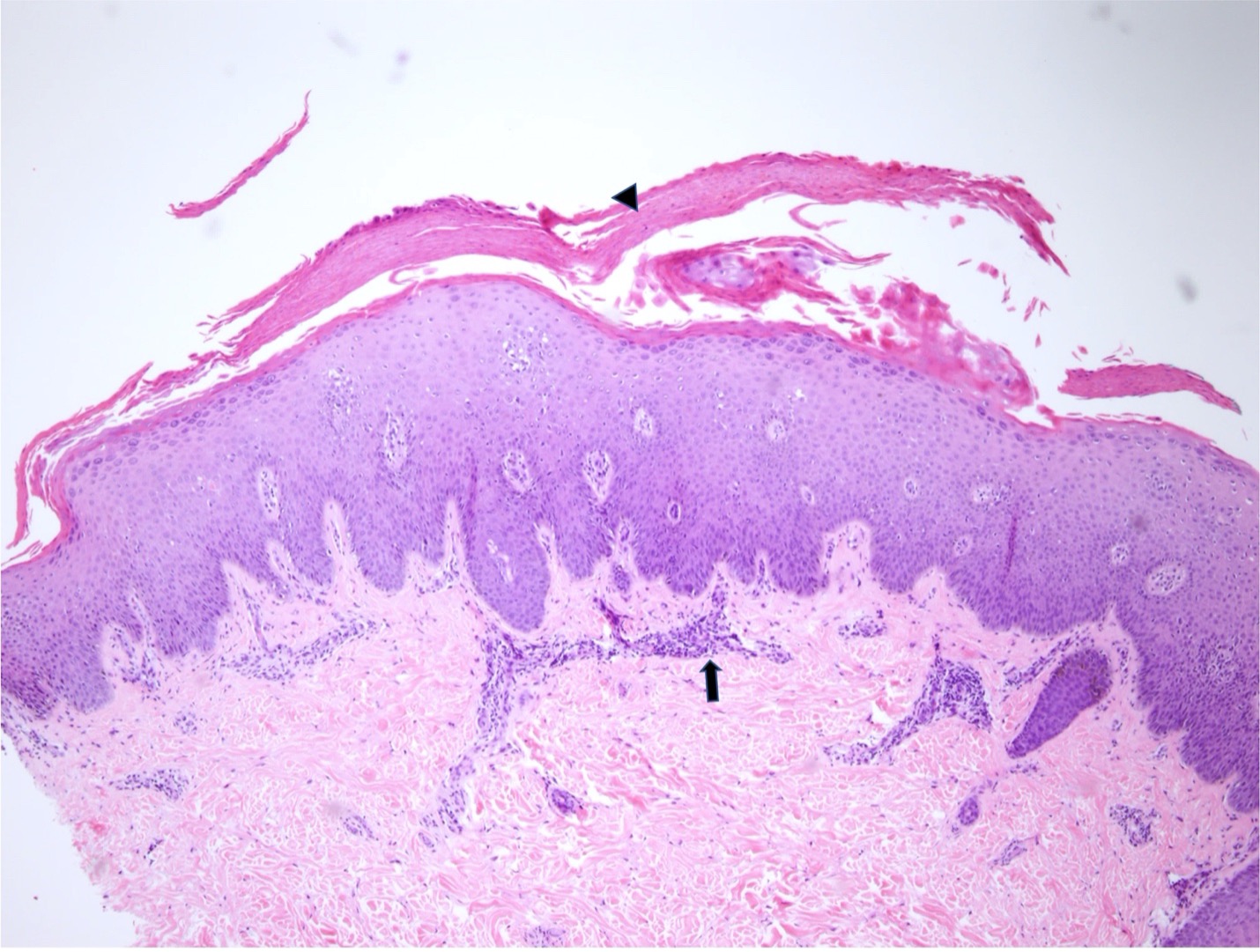

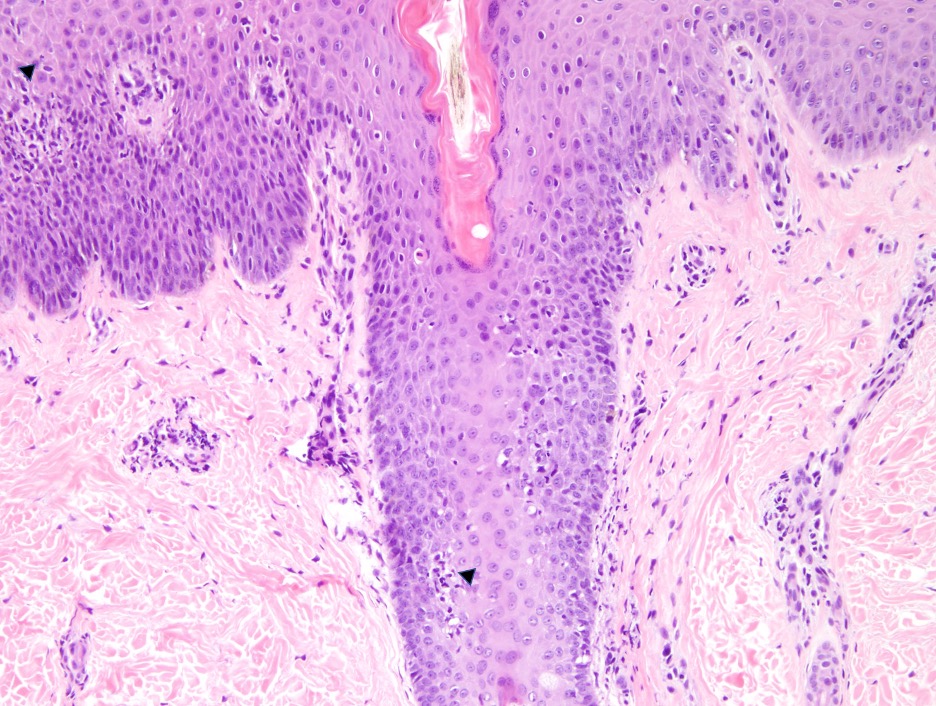

Dermatology was consulted and obtained punch biopsies of the upper and lower extremities. Pathology demonstrated psoriasiform epidermal acanthosis with mild spongiosis and exocytosis of lymphocytes. Both samples exhibited superficial perivascular and interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figures 3,4). Each biopsy was negative for fungal microorganisms. Further pathology studies were correlated with available clinical images. The patient was diagnosed with TNF-a induced psoriasiform dermatitis. The differential diagnosis included drug-induced or atypical pityriasis rubra pilaris.

The patient was started on oral corticosteroids and topical triamcinolone regimen, demonstrating interval improvement of her eruptions at three weeks. Six weeks after the initial visit, the patient completed the oral steroid taper without complication and had significant improvement of her skin eruption, especially in the scalp. She continued to use a topical steroid medication. After consulting with pediatric gastroenterology, the patient was switched from infliximab to upadacitinib for concomitant treatment of the skin eruption and UC. She demonstrated significant improvement to the trunk, extremities and head with the medication initiation and continued remission of both diseases at maintenance dosing. At her one- and three-month follow-up appointments after initiating upadacitinib, the patient had no evidence of new drug-induced eruptions. She tolerated the medication well, apart from occasional diarrhea.

This patient has been advised to avoid the TNF-a drug family to control her UC. Changing this patient’s medications appears to have resolved her skin eruptions and is effectively treating her UC.

Figure 1 (above): Dermatophytic-like skin eruptions with edema and dry scale. The patient had similar reactions on her scalp, face and behind the ears bilaterally.

Figure 2 (above): Fine, papular rash. This rash was present over the child’s back, trunk, groin and legs bilaterally.

Figure 3 (above): Psoriasiform epidermal acanthosis with mild spongiosis and mounds of parakeratosis (arrowhead) are identified. Superficial perivascular inflammation (arrow) is present. Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification: x4.

Figure 4 (above): Superficial perivascular inflammation. Mild lymphocytic exocytosis at the hair follicle and epidermis (arrowheads). Hematoxylin-eosin stain; original magnification: x10.

DISCUSSION

Upadacitinib has been studied as an effective treatment for severe or refractory UC in the adult population. Based on our information, little data is available on this medication as therapy for UC in pediatrics. This drug was indicated primarily for adult rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and AD, being approved in 2022 for UC.4,5

The change from infliximab to upadacitinib greatly benefitted our patient with an emergent skin reaction to the former drug. Studies have demonstrated between 1.7 and 35 percent of patients being treated with infliximab will develop a psoriasiform reaction.3 One study demonstrated cutaneous side effects in 20 percent of IBD patients treated with TNF-a inhibitors. Cutaneous infections and psoriasiform eruptions were the most common manifestations, with 11.6 percent of patients experiencing at least one infection and 10.1 percent developing psoriasis while undergoing anti-TNF-a treatment. These reactions correlated to treatment length and dosage.6

The study of side effects and adverse reactions of infliximab in children is limited compared to adult populations.3 One study of infliximab use in pediatrics found 11.3 percent of patients developed a cutaneous reaction, most commonly a psoriasiform reaction.3 These lesions were most frequently found in the skin folds and scalp.3 A prospective study found that in pediatric patients with IBD treated with infliximab, 47.6 percent developed an adverse skin reaction while taking the drug, half of which were ‘severe’.7 This study also demonstrated the most common location for psoriatic reactions to be the ears and scalp.7 Another retrospective review of pediatric IBD patients treated with infliximab reported 51.9 percent of skin lesions to be psoriatic reactions.8

Upadacitinib is an effective therapy for adult and pediatric refractory AD, demonstrating significant efficacy in off-label use of other skin diseases. Further, upadacitinib therapy is of increasing interest for IBD patients due to its selective inhibition of JAK1. This drug is theorized to have a decreased side effect profile and improved safety for patients compared to similar ‘pan inhibitor’ therapies like tofacitinib, which block JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 and TYK2 subunits.4 While effective therapies, drugs that inhibit a range of JAK family subunits demonstrate adverse effects; herpes zoster virus reactivation, thrombotic events, and increased blood lipid levels have been reported.5,9 Studies have also associated tofacitinib with increased malignancies.9 By targeting only JAK1, the subunit primarily associated with IBD and AD, upadacitinib is intended to have a decreased adverse event risk profile.5 In adult studies, upadacitinib has demonstrated superiority to similar biologic therapies in achieving clinical remission of moderate-to-severe UC, as well as having the best adverse event profile.5

Our case demonstrated its effective use as an alternative to infliximab in treating both UC and a drug-induced psoriasiform dermatitis with spongiotic features as effectively as it has been demonstrated to treat AD.

Consent: All patients gave consent for their photographs and medical information to be published in print and online and with the understanding that this information may be publicly available.

Disclosures: These authors report no relevant financial or nonfinancial relationships.

Grace Kennedy, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Dermatology, Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, Shreveport, LA

Brynne Tynes, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Dermatology, Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, Shreveport, LA

Ashley Barras, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Dermatology, Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, Shreveport, LA

Manasa Morisetti, MD, Department of Pathology, Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, Shreveport, LA

Areli Cuevas Ocampo, MD, Department of Pathology, Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, Shreveport, LA

Christopher Haas, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Section of Dermatology, Louisiana State University Health Shreveport, Shreveport, LA

References

1. Subedi S, Gong Y, Shi Y. Infliximab and biosimilar infliximab in psoriasis: efficacy, loss of efficacy, and adverse events. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:2491-2502. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S200147

2. Guo C, Wu K, Liang X, Liang Y, Li R. Infliximab clinically treating ulcerative colitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res. 2019;148(September). doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104455

3. Cossio ML, Genois A, Jantchou P, Hatami A, Deslandres C, McCuaig C. Skin Manifestations in Pediatric Patients Treated With a TNF-Alpha Inhibitor for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Retrospective Study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2020;24(4):333-339. doi:10.1177/1203475420917387

4. Roskoski R. Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors in the treatment of neoplastic and inflammatory disorders. Pharmacol Res. 2022;183(July):106362. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106362

5. Napolitano M, D’amico F, Ragaini E, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Evaluating Upadacitinib in the Treatment of Moderate-to-Severe Active Ulcerative Colitis: Design, Development, and Potential Position in Therapy. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2022;16(June 2022):1897-1913. doi:10.2147/DDDT.S340459

6. Fréling E, Baumann C, Cuny JF, et al. Cumulative incidence of, risk factors for, and outcome of dermatological complications of Anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: A 14-year experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(8):1186-1196. doi:10.1038/ajg.2015.205

7. Mälkönen T, Wikström A, Heiskanen K, et al. Skin reactions during anti-TNFα therapy for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: A 2-year prospective study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(8):1309-1315. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000088

8. Sridhar S, Maltz RM, Boyle B, Kim SC. Dermatological Manifestations in Pediatric Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases on Anti-TNF Therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(9):2086-2092. doi:10.1093/ibd/izy112

9. Le M, Berman-Rosa M, Ghazawi FM, et al. Systematic Review on the Efficacy and Safety of Oral Janus Kinase Inhibitors for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis. Front Med. 2021;8(September). doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.682547