A 61-year-old male presented with a three-week history of a widespread, non-pruritic rash. The rash started as pink papules on his left forearm and quickly spread to involve his trunk and legs. His primary care physician prescribed a methylprednisolone dose pack with no improvement. The patient denied any recent illnesses, new exposures, changes in personal care products, or medications prior to the onset of the dermatitis. On physical exam, there were discrete erythematous, scaly papules, some with ulcerations and hemorrhagic crust, on the chest, abdomen, back, buttocks, and bilateral upper and lower extremities (Figure 1). The palms and soles were spared.

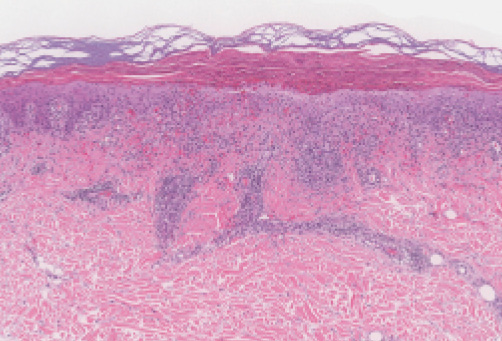

Microscopic Findings. Punch biopsies from his flank and leg showed an interface dermatitis composed of lymphocytes with a superficial and deep perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Parakeratosis, necrotic keratinocytes, pallor of the epidermis, and a hypogranular layer, along with a few extravasated erythrocytes, were also present (Figure 2). The diagnosis of pityriasis lichenoides was made.

Clinical Course. He was treated with oral doxycycline 100mg twice a day and topical triamcinolone 0.1% ointment. The patient had significant improvement after three months of treatment (Figure 3).

Discussion

Pityriasis lichenoides is a self-limiting papular, clonal T-cell disorder that exists on a disease spectrum. Within this spectrum, cases may be classified as pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA), the acute form, or pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC), the chronic form.1 Pityriasis lichenoides has a slight male predominance, with approximately 56.6 percent male predominance of adult cases.2 The highest prevalence of disease onset occurs in the third decade of life.1 The etiology is undetermined, but it is hypothesized to be a response to a foreign antigen.1 There have been reported associations with infections, medications, vaccines and radiocontrast dye.1,3,4

Clinically, pityriasis lichenoides presents as recurrent crops of erythematous papules that spontaneously regress over several weeks. The individual papules may form scale crust and ulcerate. Patients can have both acute and chronic lesions that vary widely in duration from weeks to months, demonstrating the continuum of acuity and chronicity possible in pityriasis lichenoides.1 Patients with widespread distribution of their lesions tend to have a shorter disease course, averaging 11 months, as opposed to patients with a peripheral distribution of lesions, averaging 33 months.5 Unfortunately, pityriasis lichenoides can be chronic and relapsing with relapses sometimes separated by long periods of remission.1

Histologically, pityriasis lichenoides is a superficial, perivascular interface dermatitis, with extravasated erythrocytes and focal parakeratosis often noted. A wedge-shaped infiltrate of lymphocytes and occasional neutrophils is located in the upper and middle dermis.1,2 Some classify pityriasis lichenoides as a T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder, and T-cell receptor gene rearrangement (TCR) has shown monoclonality in 52-65 percent of cases.6 Importantly, there are reports of patients with pityriasis lichenoides who subsequently develop mycosis fungoides.

Authors report risk factors being a positive TCR, atypical patches and plaques, marked lymphocytic nuclear atypia, and diminished CD7 and CD8 cell counts.6 Given this, it is advisable that patients continue to be clinically monitored, and the clinician should have a low threshold to re-biopsy if there is variation from the expected disease course. However, the majority of patients with positive TCR do not progress to a cutaneous lymphoma, and positive TCR rearrangement is seen even in benign conditions, such as pityriasis lichenoides.6,7

Current therapy recommendations are based primarily on case studies and anecdotal reports due to the rarity of disease. Treatment generally consists of topical corticosteroids, tetracyclines, and narrow-band UVB phototherapy (NB-UVB). Topical corticosteroids have been shown to alleviate pruritus but do not change the overall disease course.8 Tetracyclines are used for their anti-inflammatory properties; their initial use was due to a report in 1974 that hypothesized PLEVA was a hypersensitivity reaction to an infectious agent.9 More recently, studies have demonstrated complete remission with NB-UVB therapy.10,11 However, relapse is common and can occur in as many as 46 percent of cases in the 6 months post-treatment.11

The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Bowers S, Warshaw EM. Pityriasis lichenoides and its subtypes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Oct;55(4):557-572.

2. Willemze R, Scheffer E. Clinical and histologic differentiation between lymphomatoid papulosis and pityriasis lichenoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985 Sep;13(3):418-428.

3. Klein PA, Jones EC, Nelson JL, Clark RA. Infectious causes of pityriasis lichenoides: a case of fulminant infectious mononucleosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003 Aug;49:S151-3.

4. Baykal L, Arıca DA, Yaylı S, et al. Pityriasis Lichenoides Et Varioliformis Acuta; Association with Tetanus Vaccination. J Clin Case Rep. 2015 Jan 28;5:518.

5. Wood GS and Reizner GT. Other Papulosquamous Disorders. In: Bolognia, JL, ed. Dermatology, 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2012. 159-62.

6. Zaaroura H, Sahar D, Bick T, Bergman R. Relationship between pityriasis lichenoides and mycosis fungiodes: A clinicopathological, immunohistochemical, and molecular study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017 Nov 22;Epub ahead of print.

7. Plaza JA, Morrison C, Margo C. Assessment of TCR-beta in a diverse group of cutaneous T-cell infiltrates. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(4):358-365.

8. Neide P, Brinca A, Brites MM, et al. Pityriasis Lichenoides et Varioliformis Acuta: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2012 Jan-Apr;4(1):61-65.

9. Piamphongsant T. Tetracycline for the treatment of pityriasis lichenoides. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91(3):319-22.

10. Park J, Jwa S, Song M, et al. Is narrowband ultraviolet B monotherapy effective in the treatment of pityriasis lichenoides? Int J Dermatol. 2013:52(8):1013-18.

11. Fernández-Guarino M, Aboin-Gonzalez S, Cuidad Blanco C, et al. Treatment of adult diffuse pityriasis lichenoides chronica with narrowband ultraviolet B: experience and literature review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2017 Apr;42(3):303-305.